PART 1 PART 2

The CES ultra underscores its use of its conductive rubber ear clips. The rationale behind it is some interesting science on the ear; especially the vagus nerve and the special role it plays in the body. Read on.

Ref: Wandering nerve could lead to range of therapies

Taking Heart

The vagus nerve has profound control over heart rate and blood pressure. Patients with heart failure, in which the heart fails to pump enough blood through the body, tend to have less active vagus nerves. Trying to correct the problem with electrical stimulation makes sense, says Michael Lauer, director of the cardiovascular sciences division at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute in Bethesda, MD. “It’s a great idea.”

Yet so far, results from studies on the effects of vagus stimulation on heart failure have been inconsistent. In 2011, researchers reported in the European Heart Journal that repeated vagus nerve stimulation improved quality of life and the heart’s blood-pumping efficiency in heart failure patients. A vagus stimulation trial of heart failure patients in India published in the Journal of Cardiac Failure in 2014 echoed these results. After six months of therapy, the patients’ left ventricles pumped an average of 4.5 percent more blood per beat.

Last August, however, researchers reported that a six-month clinical trial of vagus stimulation failed to improve heart function in heart failure patients in Europe. This study had the most participants — 87 — but used the lowest average level of electrical stimulation. “All the results thus far are preliminary. The studies that have been finished to date are relatively small,” Lauer says. “But there certainly are promising findings that [suggest] we may be barking up the right tree.”

Another group of scientists is testing more intense vagus stimulation for patients with heart failure. The trial, called INOVATE-HF, is funded by the Israeli medical device company BioControl Medical and uses a higher level of electrical current than the European study that showed no measurable improvements.

“If you try to lower blood pressure and you take a quarter of a pill instead of one pill, blood pressure won’t change,” says cardiologist Peter Schwartz of the IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano in Milan. It’s equally important to use the right dose of vagus stimulation, he says. The new trial is also much larger than earlier studies, with more than 700 patients enrolled internationally. Results are expected by the end of 2016.

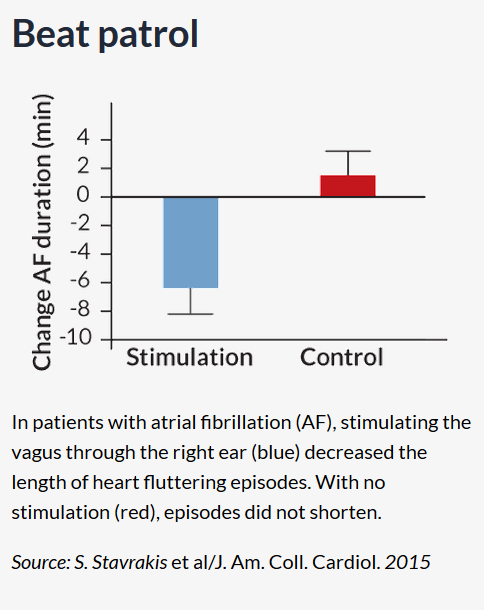

Vagus manipulation isn’t limited to heart failure research. It’s also being tried in atrial fibrillation, in which the heart flutters erratically. “When it flutters, it doesn’t really push blood very efficiently,” says clinical electrophysiologist Benjamin Scherlag of the University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City. Atrial fibrillation is common in people over age 60, Scherlag says, and can ultimately lead to blood clots and strokes. Treatments include drugs that alter heart rhythm or thin the blood, but they don’t work for all patients and some have nasty side effects, Scherlag says.

In the lab, scientists can use high-intensity vagus stimulation to alter heart rhythm and induce atrial fibrillation in animals. But milder stimulation that alters heart rate only slightly, if at all, can actually quell atrial fibrillation, animal studies and one human study show.

Vagus stimulation for atrial fibrillation is still in its infancy, and clinical applications haven’t been adequately tested, says Indiana’s Zipes. “Nevertheless, the concept bears looking into.”

Skin Deep

“Vagal nerve stimulation is very nice, but in order to get to the vagus nerve … you have to cut down surgically,” Scherlag says. “This is not the kind of thing you want to do, except under extreme situations.”

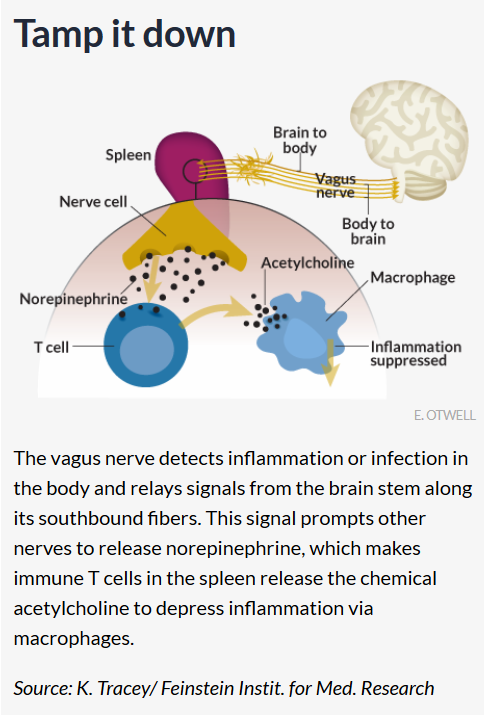

But in the ear, tiny fingers of the vagus’s fibers run close to the surface of the skin, primarily under the small flap of flesh, the tragus, that covers the ear’s opening. Studies have explored using stimulation of those fibers through the skin of the ear to treat heart failure, epilepsy and depression, as well as memory loss, headaches and even diabetes — a reflection of the nerve’s control over a variety of hormones in addition to acetylcholine and norepinephrine.

Stimulating the vagus nerve through the ear of diabetic rats lowered and controlled blood sugar concentrations, researchers from China and Boston reported in PLOS ONE in April. The stimulation prompted the rats’ bodies to release the hormone melatonin, which controls other hormones that regulate blood sugar.

Ear-based vagus stimulation appeared to improve memory slightly in 30 older adults in the Netherlands. After stimulation, study subjects were better able to recall whether they had been shown a particular face before, says study coauthor Heidi Jacobs, a clinical neuroscientist at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. The researchers, who reported the work in the May Neurobiology of Aging, plan to investigate whether these effects last over time and exactly how the stimulation affects the brain, Jacobs says.

The ear isn’t the only nonsurgical target. The company electroCore, based in Basking Ridge, N.J., manufactures a small, handheld device that can stimulate the vagus when placed on the throat. The company initially tested the devices to reduce asthma symptoms — relying on the nerve’s anti-inflammatory action. But during testing, patients reported that their headaches were disappearing, says J.P. Errico, CEO of electroCore. Now, the company is investigating the use of an electroCore device to treat chronic cluster headaches, severe headache attacks that can come and go for over a year. People suffering from an average of 67.3 cluster headaches each month experienced around four fewer attacks per week on average when using the device along with standard treatments like drugs, researchers reported in Cephalalgia in September.

Beyond the Mystery Switch

Even for depression and epilepsy, Tak says, researchers still need to figure out the best ways of stimulating the vagus — exactly where to place a device, and how much of a shock to deliver.

The nerve’s multitasking, two-way nature makes it a challenge to fully understand and control. It’s hard to know exactly what you’re zapping when you stimulate the vagus nerve, says physiologist Gareth Ackland of University College London. He compares vagus stimulation to flipping on a light switch in one room of a house and discovering that this endows other rooms in the house with magical powers. “I’m not sure which room it’s going to happen in, I’m not sure for how long and I’m not sure if, after a while, it’s going to work or not,” he says.

The intensity of electrical current, duration of stimulation and each patient’s health status could all affect the results of a vagus stimulation trial, Ackland says. And it’s possible that a widespread effect, such as suppressing inflammation caused by the immune system, could even be harmful to some patients.

Ackland says that he and his colleagues agree that the vagus nerve is important. And he’s not ready to discount vagus stimulation as a potential therapy for conditions such as heart failure. But he warns that there’s a good deal of biology left to understand. “There’s an awful lot of basic science and basic clinical research that is needed before launching into a variety of potential interventions,” he says.

For Tracey, it’s about way more than the vagus. “Nobody should overpromise that the vagus nerve is the secret to everything,” he says. But with a better map of the body’s nerves and their functions, the lessons learned by studying the vagus could inform future therapies that use nerve stimulation, he says. If researchers can understand and manipulate a particular circuit in a nerve that controls a specific molecule — for example, a protein involved in pain or even cell division — they could zero in on crucial targets. “The promise,” he says, “is for tremendous precision.”

Go back to PART 1