“Why do some people age more ‘successfully’ than others?” UC Berkeley researchers think sleep is one of the factors.

As people get older, they sleep less and wake up more frequently. But does that mean older people just need less sleep?

Not according to UC Berkeley researchers, who argue in an article published April 5, 2017 in the journal Neuron that the unmet sleep needs of the elderly elevate their risk of memory loss and a wide range of mental and physical disorders.

The review suggests aging adults may be losing their ability to produce deep, restorative sleep. Furthermore, older people are likely paying for lost sleep both mentally and physically, the reviewers argue.

“Sleep changes with aging, but it doesn’t just change with aging; it can also start to explain aging itself,” says review co-author Matthew Walker, who leads the Sleep and Neuroimaging Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. “Every one of the major diseases that are killing us in first-world nations—from diabetes to obesity to Alzheimer’s disease to cancer—all of those things now have strong causal links to a lack of sleep. And all of those diseases significantly increase in likelihood the older that we get, and especially in dementia.”

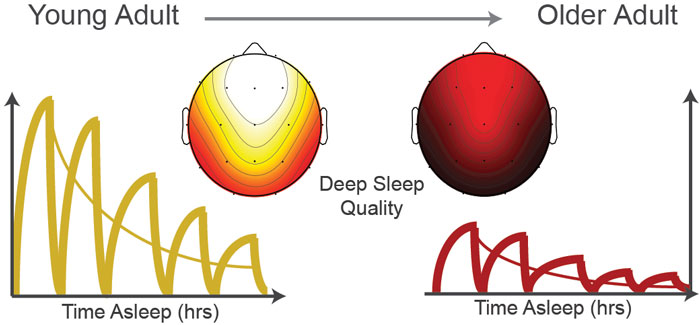

Older adults’ sleep loss isn’t due to a busy schedule or simply needing less sleep. As the brain ages, neurons and circuits in the areas that regulate sleep slowly degrade, resulting in a decreased amount of non-REM sleep. Since non-REM deep sleep plays a key role in maintaining memory and cognition, that’s a problem. “There is a debate in the literature as to whether older adults need less sleep, or rather, older adults cannot generate the sleep that they nevertheless need. We discuss this debate at length in the review,” says Walker. “The evidence seems to favor one side—older adults do not have a reduced sleep need, but instead, an impaired ability to generate sleep. The elderly therefore suffer from an unmet sleep need.”

This problem has long flown under the radar in sleep research. Older adults rarely report feeling sleepy or sleep-deprived on surveys but that may be because their brains are accustomed to being sleep-deprived every day. When researchers look for chemical markers of sleep deprivation, older adults have them in spades, and when researchers measure the brain waves of older adults, they often find that key electrical patterns in sleeping brains—such as “slow waves” and “sleep spindles”—are disrupted.

Perhaps even more distressingly, the changes in sleep quality start well before people notice that they are shifting to a more “early-to-bed-early-to-rise” schedule or are waking up in the middle of the night more often. The loss of deep sleep starts as early as the mid-thirties. “It’s particularly dramatic in early middle age when it starts to begin,” says Mander. “The difference between young adults and middle aged adults is bigger than the difference between middle aged adults and older adults. So there seems to be a pretty big change in middle age, which then continues as we get older.”

Another surprising finding the authors address is the resilience of REM sleep to the process of aging—rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep, where dreams occur. “It does decline, but it is nowhere near as dramatic as the decline in deep non-REM sleep,” says Walker. “So the question then becomes: why is deep non-REM sleep more vulnerable?”

The authors stress that there is variability between individuals when it comes to sleep loss. Women seem to experience far less deterioration in non-REM deep sleep than men, even though the changes to REM sleep are about the same in those two genders. (Aging-related sleep loss hasn’t been studied in trans and nonbinary people yet.) Faster-than-average sleep deterioration may also be a key risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and dementia.

If older people are sleeping a little less than they used to — or wake up once at night then quickly fall back asleep — that’s probably not a red flag. But older adults should talk to their doctor if they routinely sleep less than six hours a night, or lack long “consolidated” blocks of sleep. “We need to recognize the causal contribution of sleep disruption in the physical and mental deterioration that underlies aging and dementia. More attention needs to be paid to the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disturbance if we are going to extend healthspan, and not just lifespan.”

The Hunt for New Treatments

Meanwhile, non-pharmaceutical interventions are being explored to boost the quality of sleep, such as electrical stimulation to amplify brain waves during sleep and acoustic tones that act like a metronome to slow brain rhythms.

However, promoting alternatives to prescription and over-the-counter sleep aids is sure to be challenging.

“The American College of Physicians has acknowledged that sleeping pills should not be the first-line kneejerk response to sleep problems,” Walker said. “Sleeping pills sedate the brain, rather than help it sleep naturally. We must find better treatments for restoring healthy sleep in older adults, and that is now one of our dedicated research missions.”

But people should not wait until old age to care about sleep. People often start losing the capacity for deep sleep in middle age, and that decline continues over the years. In some cases sleep apnea may be to blame. In other cases, people may need lifestyle adjustments that can improve their sleep. The good news is that “behavioral and environmental changes are powerful.” People can improve their sleep by fitting physical and social activity into their daily routine. At night they make sure the bedroom temperature is comfortable and limit exposure to artificial light — especially the blue glow of computer and TV screens. It’s important to have enough daylight, in the morning and afternoon: That helps keep the body’s circadian rhythms (the sleep-wake cycle) on track.

Also important to consider in changing the culture of sleep is the question of quantity versus quality.

“Previously, the conversation has focused on how many hours you need to sleep,” Mander said. “However, you can sleep for a sufficient number of hours, but not obtain the right quality of sleep. We also need to appreciate the importance of sleep quality.

“Indeed, we need both quantity and quality”

REF> news.berkeley.edu, medicalxpress.com/news