The treatment seemed as ridiculous as wearing a foil hat to block CIA transmissions: 20 patients with overactive bladder syndrome had electrodes stuck to the soles of their feet for three hours every evening, producing a gentle vibration and causing the big toe to rhythmically bend and straighten.

But after a week or so, the patients’ symptoms had improved more than typically happens with medication, University of Pittsburgh researchers will report at a scientific meeting next month. The patients needed to dash to the bathroom a bit less often and suffered half as many accidents, all without the constipation, dry mouth, and other side effects of standard drugs.

The finding, though preliminary, adds to evidence that therapies for a wide range of ills might come not from medications but from electricity.

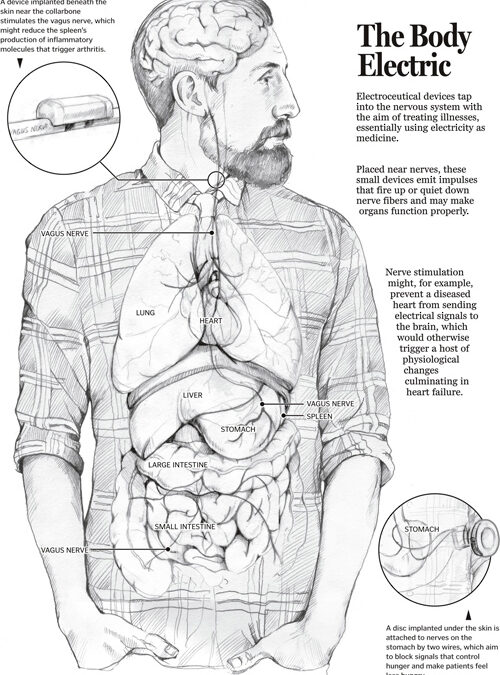

Scientists worldwide are exploring the potential of devices dubbed electroceuticals to treat conditions from heart failure and asthma to diabetes, incontinence, and arthritis. The first of the new class of devices, to treat obesity, reached the market this year, and the US government and drug companies are pouring tens of millions of dollars into further research. Enthusiasm for electroceuticals has reached the point that, at a science meeting this year, a researcher listing their many purported benefits jokingly included world peace.

But the excitement is rooted in a small number of studies with relatively few patients, and researchers don’t understand many of the basics about the body’s electrical highways. The field is filled with what several scientists called “cowboys” and with researchers who are “just throwing electric darts at things without knowing what they’re doing,” as one scientist said.

Ranging in size from an iPod to a pencil eraser, electroceuticals are placed on the skin or surgically implanted, where they emit electrical impulses that fire up or quiet down neurons — nerve fibers. Minuscule electric currents normally pulse through nerves to keep the heart, airways, stomach, and other organs functioning and could, potentially, zap them back from malfunctioning.

Unlike drugs, which flood the body with a chemical, electroceuticals promise to be targeted and, proponents argue, virtually free of side effects.

“Everyone wants to use devices to replace drugs,” said neurosurgeon Kevin Tracey, president of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research on New York’s Long Island. “Every cell in the body is within shouting distance of sensory neurons, so in principle bioelectronics have great potential.”

Hoping to narrow the gulf between principle and reality, the National Institutes of Health will announce this autumn the first funding from its $248 million Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions, or SPARC, program, and the Pentagon’s blue-skies research arm, DARPA, will disclose recipients of its $80 million ElectRx initiative. The program is part of the Defense agency’s year-old biotechnology unit, which aims to advance discoveries to help wounded warriors and others.

GlaxoSmithKline, the pharmaceutical company, is investing $50 million in bioelectronic startups and $5 million more for basic research to, among other things, map the body’s neurons and show how they might affect chronic diseases, said Kristoffer Famm, who heads the program.

The potential of electrical impulses to treat disease is based on the fact that the body is one big circuit board.

Neurons wend their way into and out of organs like threads in ornate medieval tapestries. As a result, contrary to traditional medical devices such as heart pacemakers that target malfunctioning organs directly, electroceuticals could work long-distance, stimulating neurons far from disease sites.

The tibial nerve near the ankle, for instance, is connected to nerves in the pelvis. Electrically stimulating the former can alleviate chronic pelvic pain, small studies have shown. It has not escaped scientists’ attention that stimulating one point in the body to treat a problem at another is the basis for acupuncture.

The long-distance champion is the vagus nerve, which runs from the brain into every major organ via 100,000 or so branches. That offers both opportunity and risk. The vagus could serve as a therapeutic target for many diseases. But stimulating such a peripatetic nerve could produce “off-target” effects.

“The vagus innervates so many organs, you may be treating obesity but wind up affecting blood pressure,” said gastroenterologist Richard McCallum of Texas Tech University.

Among its many jobs, the vagus carries commands from the brain telling the stomach to expand to receive food and the gastrointestinal tract to process that food. That makes it an inviting target for obesity treatments. Blocking vagal activity interrupts the brain’s commands, said Katherine Tweden, a vice president at Minnesota-based EnteroMedics.

“People physically cannot eat as much and they stay fuller longer because the food doesn’t move out of the stomach as quickly,” she said.

In July, EnteroMedics reported that 162 obese volunteers who received the company’s vBloc electronic device below the esophagus lost about one-quarter of their excess weight after 12 and 18 months. That was only somewhat better than in volunteers who got a sham device, however, leaving the clinical trial short of its goal. Nevertheless, the US Food and Drug Administration had approved the device in January.

One of the most anticipated electroceutical studies stems from a chance 1998 discovery, by the Feinstein Institute’s Tracey, that electrically stimulating the vagus nerve in rats can slash the spleen’s production of inflammatory molecules.

That made him wonder: Could bioelectronics treat inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis? In 2011, a company he cofounded, California-based SetPoint Medical, launched a small trial in Europe to find out. A device the size of a stubby pencil and implanted below the collarbone painlessly zaps the vagus for a minute once or twice a day.

More than half the 18 patients saw a reduction of their arthritis symptoms, gaining the ability to fasten buttons, use forks, and garden without pain, SetPoint chief executive Anthony Arnold said.

Scientists are withholding judgment until SetPoint publishes peer-reviewed results, but some are skeptical. Like many early-stage studies, the trial does not include a control group, noted Brendan Canning of Johns Hopkins University, who is investigating whether electrical stimulation can treat respiratory diseases. It therefore cannot rule out the possibility that improvements in arthritis symptoms reflected not the electrical jolt but patients’ expectations.

The body’s electrical byways are two-way streets, so electroceuticals could also target nerves leading away from a malfunctioning organ — such as the heart.

When the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs, it sends the brain an SOS. The brain in turn triggers a host of responses that are meant to be protective but can backfire: the heart muscle might develop scars, and the lungs accumulate fluid, causing more deaths than the heart’s initial malfunction.

“That suggests that if you intervene in this downstream process, you can prevent many of the serious consequences of heart failure,” said physiologist Irving Zucker of the University of Nebraska. When he and his team did that in rats whose heart failure should have been fatal, they reported last year, the animals remained alive.

A human study based on the idea — using an implant from Minneapolis-based CVRx to stimulate nerves leading from the heart to the brain — is raising hopes that what worked in rats could work in people.

Other electroceuticals for heart disease have flamed out, however. Last year, Massachusetts-based Boston Scientific reported that patients who received its implanted device, which stimulated the vagus nerve in the neck, showed no improvement compared with control patients.

That was a serious setback for the field, leading even proponents to call for more basic research into its scientific underpinnings.

“There is no doubt that current devices are sometimes able to elicit a response,” said SPARC coordinator Danilo Tagle, “but it’s hit or miss.”

This story was produced by Stat, a national publication from Boston Globe Media Partners that will launch online this fall with coverage of health, medicine, and life sciences.